1. The High-Stakes Reality of “Exactly-Once”

Imagine it is New Year’s Eve. Demand is peaking at 50,000 requests per second. A user requests a ride, but the app lags. They hit the “Request” button three times. In a naive system, this triggers three separate payment authorizations, locking the user’s funds and potentially draining their bank account before the ride even starts.

For a company like Uber, payment consistency isn’t just about billing—it is the bedrock of trust. A “double spend” or a “lost write” in the driver’s payout ledger doesn’t just mean a refund ticket; it means legal liability and driver churn. At scale, standard database transactions ($ACID$) struggle to maintain performance across distributed regions. This lesson explores how Uber solves this using an Immutable Ledger Architecture (internally known as Gulfstream).

2. Core Concept: The Append-Only Double-Entry Ledger

The intuitive leap here is moving away from “database as a State Store” (e.g., UPDATE users SET balance = 50) to “database as a History Log.”

The Mechanism

In a high-frequency payment system, you never overwrite data. You only append new events. This is based on Double-Entry Bookkeeping, a 500-year-old accounting principle adapted for distributed systems.

- Immutable Entries: Every transaction is recorded as two entries: a debit from one account and a credit to another.

- The Equation:

Sum(All Entries) = Current Balance. - Version Hashing: Each entry contains the hash of the previous entry, forming a cryptographic chain (similar to a private blockchain) that prevents tampering or reordering.

Step-by-Step Flow

- Intent: The Rider App sends a

Chargerequest with a uniqueidempotency_key. - Locking: The system doesn’t immediately move money. It creates a

HOLDentry on the rider’s ledger. - Validation: The system sums the rider’s history (or uses a cached snapshot) to ensure

Balance - Hold >= 0. - Capture: Once the ride completes, a

CAPTUREentry is appended, finalizing the movement to the Driver’s ledger.

3. Critical Insights

Common Knowledge: Most engineers know about Idempotency Keys. These are unique tokens (UUIDs) sent by the client. The server checks a high-speed store (like Redis) to see if it has already seen this key. If yes, it returns the previous successful response without re-processing.

Rare Knowledge: The “Leftover” Hold Problem A major failure mode occurs when a HOLD is placed, but the ride is cancelled or the network times out. If the system fails to issue a RELEASE event, the user’s funds remain locked indefinitely. Advanced implementations use Time-To-Live (TTL) based expiry events—a background reaper process that scans for “stale holds” and automatically appends a VOID entry after 30 minutes.

Advanced Insight: Optimistic Locking with CAS (Compare-And-Swap) At 2026 scale, pessimistic row locking (locking the user’s row in Postgres) causes massive contention. Instead, Uber uses Optimistic Locking.

- Read the current

version_idof the account. - Calculate the new state.

- Write only if

version_idhasn’t changed. - If it has changed (meaning another concurrent transaction succeeded), retry the calculation.

Strategic Impact: Reconciliation as a First-Class Citizen No distributed system is perfect. Messages drop. Kafka partitions lag. Uber runs a massive offline reconciliation process (using Spark/Flink) that replays all logs from the payment gateway and compares them against the bank statements and the internal ledger. This “detective” system runs T+1 (one day later) to catch any drift that the real-time system missed.

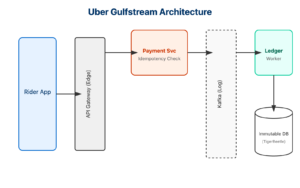

4. Real-World Example: Uber’s Gulfstream

Uber’s payment platform, Gulfstream, manages this complexity.

- Challenge: Handling over 25 billion payment orders.

- Solution: They migrated from a monolithic database to a sharded, event-driven architecture. They use Kafka for event ingestion and a custom ledger built on top of storage engines like Schemaless (Uber’s MySQL wrapper) or modern equivalents like TigerBeetle.

- Key Win: By decoupling the “Payment Intent” from the “Money Movement,” they allowed the Ride service to proceed even if the Banking Rail was temporarily slow, relying on the ledger to settle eventually.

5. Architectural Considerations

- Observability: You must log the state transitions of a payment (e.g.,

INIT->AUTHORIZED->CAPTURED). If a payment is stuck inAUTHORIZEDfor > 1 hour, fire an alert. - Cost: Storing every single debit/credit entry forever is expensive. Use Tiered Storage: Keep the last 90 days in hot storage (NVMe/ScyllaDB) and offload older history to cold storage (S3/Iceberg), relying on “Snapshot” entries to carry the balance forward.

- When to avoid: For simple low-volume apps, this is over-engineering. A standard SQL transaction is sufficient for < 100 TPS.

6. Practical Takeaway

To truly understand this, you need to see the race conditions in action. The accompanying demo simulates a high-concurrency environment where multiple threads try to charge a single wallet simultaneously.

Next Steps:

- Run

bash setup.sh. - Open the dashboard at

http://localhost:5000. - Use the “Flood Attack” button to send concurrent requests.

- Observe how the Idempotency Check rejects duplicates and protects the ledger integrity.